|

I once started a job in July and gave notice five days later. I was miserable – it was not what I wanted to be doing; wrong environment; not the place for me. All these things I said to the HR manager, the same guy who hired me. He understood – these things happen. But as for the notice – would I be willing to stay until they found my replacement? Of course I would – it’s the right thing.

I remember vividly the feeling of sweet relief after walking out of his office. Now I could relax… and enjoy the job. And then become quite good at it. I stayed all summer. Eventually I transferred to a North Carolina office. Eventually I worked there for seven years. That was my first clue that I shouldn’t “trust my gut.” Being overwhelmed translated to insecurity, which morphed into the belief “I’ve made a huge mistake.” That exact sentiment, the “huge mistake,” has surfaced often, accompanying life-changing events including, but not limited to, marrying Mike, becoming a mother, and Pilates instructor training. So when I am seized by the desire to “give notice,” mentally, I do. In my mind, I convince myself that I am no longer required to do this – and this gives me the freedom to move forward, without worry of failure. I honestly don’t know if they even looked for my replacement at that first job. Maybe that HR guy knew, in his gut, that I was being misdirected by mine. That all I needed to do was “quit” to take the pressure off, and I’d be fine. That I was simply scared. But I know now what lives in my gut, so if my gut says “get out,” it’s really the fear talking – fear, which I no longer let take the wheel.

4 Comments

The truth was, I was relieved to be kicked out of the church, just like I’d been relieved to be kicked out of my cousin-in-law’s wedding, and for the same reason.

That’s not to say I wasn’t ashamed, both times. I was horribly ashamed, and embarrassed – but I had it coming. I was profoundly unhappy in my marriage and was no longer willing – not for friends, family or even Jesus – to keep it going. Excommunicated was the word I used, as it lent a hint of drama to the situation. Actually, it was a simple conversation. The minister explained that, if I pursued divorce I wouldn’t be following the church’s teachings and could no longer be welcome. I think my tears in that moment made him hopeful, that perhaps he was finally reaching me with this revelation of what I would be losing. I was saved, the deal was closed, but in truth, it never really took. It was a bad match, much like the marriage crumbling beneath me. My relationship with Jesus was going the way of my marriage – built on good intentions, colliding with unmet expectations and finally wrecked by lies. I was breaking up with two good men – both of whom I’d been a disappointment to, and was sincerely relieved to be released from. Church members tried to convince me, talk me out of my choice, save me from myself. Even the minister’s wife tried, but I got the sense she understood better than anyone. My precariously perched soul was finally given up on, and in the end, it didn’t seem to be hard for most of them to let me go. Nor was it hard for me to go. It never fit me – like the baptismal robe, it was too heavy, even before it got wet. He drank coffee, black. Breakfast, lunch, dinner – whenever we went out to eat, it was his beverage order.

I never once heard him complain about the coffee, any coffee, anywhere he got it. Back then my father drank every cup of coffee with the same level of expectation, much like he seemed to approach everything else – just happy to get it. For most of that time I was completely unaware that coffee could be good or bad. It always smelled good to me, one of the few smells I could identify, like peanut butter or Lucky Strikes. But now – now I know crappy coffee when I swallow it, and I know there is a lot of it out there. We didn’t have a coffee maker. We did have a percolator, but only used it on special occasions, or for company. My mother drank hot tea. We all drank tea, like the Canadians who drank tea like the English, with milk and sugar. We had a kettle on the stove and a teapot nearby. We drank Red Rose tea – a Canadian tea that Granny would bring with her on visits, or my mother would stockpile when we were in the country to visit her family. My father drank instant coffee. I realized later that it was nasty tasting stuff, especially in comparison to brewed coffee. Even the best instant coffee tastes like feet. He worked on construction and had a bad fall, resulting in, among other things, the loss of his taste and smell. In the years to follow, when Kathy or I would ask my father if he liked what he was eating or drinking, my mother would point out that he couldn’t really taste anything, so why did we even bother to ask? Maybe we were just being polite. I dreaded it. Not just spending the money, but the process. It was going to be a drag – inconvenient, messy, and invasive. It would be difficult to keep things organized, impossible to keep things clean. And we had lost Michael. We were going ahead with this big project – his design, his plans – without him, and it was going to be horrible and sad.

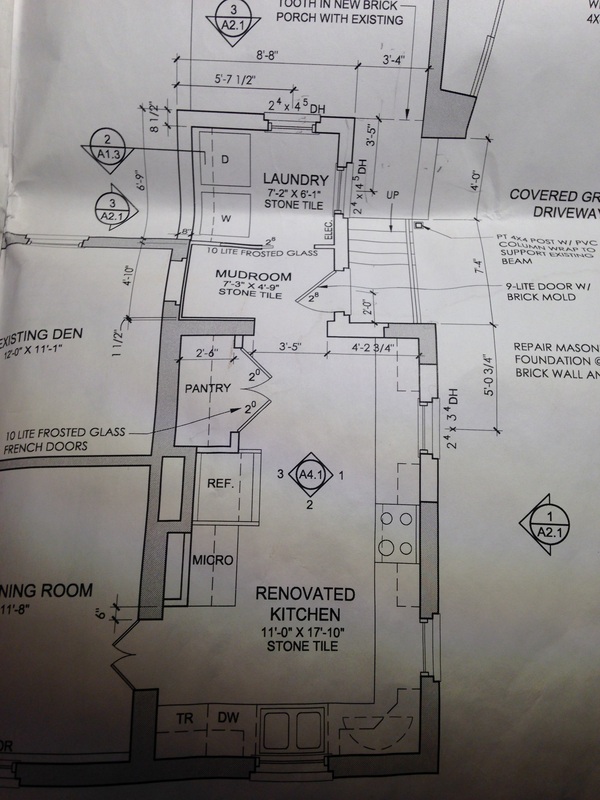

But then we met Ray, and he brought in Matt and Jim, Dean, Shon, and Ernie the tile guy and Neville the painter and they were all considerate and professional – men of great skill and meticulousness. And then we met another Michael – Ray’s son – and he became the guy who showed up at our house every day, and he answered our questions and made suggestions and was patient and got things done. And it wasn’t horrible or even just tolerable, but actually pleasant. From September 2013 until March 2014 – six months, as predicted. Our refrigerator was in the dining room, microwave in the den, toaster oven in the exercise room. Washing spoons in the bathroom, eating off paper plates and out of paper bowls. And the cat jumping out open doors and windows every chance he got – all those guys chasing him down to retrieve him and bring him back inside. Then no washing machine for six weeks, carrying laundry across town with pockets full of quarters, or occasionally to the homes of generous neighbors. And then, finally and suddenly, it was done. We had an amazing new kitchen. And a master bathroom with a door, a laundry room and a mudroom. And a rebuilt carport and brick patio. They were finished, the project complete. And they packed their tarps and tools and equipment into trucks and drove away. And I felt sad to see them go. My first friend was my best friend and was until she became my longest friend, which she remains.

We became friends by virtue of geography – she lived next door. She, a year older than me, a year younger than Kathy, prettier than either one of us, introduced me to Bruce Springsteen. I was in her wedding, she was in mine. We have friends; we disconnect and reconnect again, as life allows. Once, in high school, I yelled at one friend in a righteous fit of defense of another and made her cry; I was harsh, and feel perpetually sorry for that blunder. I’ve been a friend to some who were not my friend, but never seemed to notice. It’s hard to break up with a friend, even harder than breaking up with a lover. Wendy made me add color to my life. Karen made me want to teach Pilates. Ginny made me see the humor of honest self-awareness. With Dawn, I share books; with Noelynn, music. And with both, the particular joy/frustration of parenting. Hope opens my heart to poetry; Mary Jo’s writing unravels me. And Valley makes me write – even about those things I could never ever write about. And Kathy – if I don’t share it with her, it doesn’t seem real – whatever it may be. No matter what we do, or who we are, we don’t get there alone. And if we are lucky, we realize that. Oswego friends, Syracuse friends, North Carolina, school, work, life – I keep my them with me. I’ll paraphrase that ridiculously violent NRA slogan –You can have my friends when you rip them from my cold, dead hand. Because the thing that remains is how deeply I appreciate these people, and how determined I am to keep them close, regardless of life’s obstacles. I knew little of the story; I didn’t even know this much when I was young.

And then I heard more. The story told by the younger sister, about how much she adored her older brothers. About how her oldest brother paid for her piano lessons when her parents couldn’t afford to. About how he helped her and her fiancé buy a car. About how much he did for their parents, helping with projects and the upkeep of their house. Then about how he married a Canadian girl when he was 31, and hardly ever came home again. I had heard that story, but it was a different version. It was the story of the Canadian girl who was not welcome in her fiancé’s home, because she was Canadian, because she came from a “broken home,” because she wasn’t good enough. He and the Canadian girl moved to Niagara Falls, had a daughter, then to Oswego and had another. He didn’t see his family much after that, and as the girls grew up, they were told that his family didn’t want to see them. They heard that his sister and her husband thought “they are better than us; they don’t want anything to do with us.” And because the story came from the girls’ mother, of course they believed it. They didn’t hear the story about the early lives of the two young boys; they never heard the story about the piano lessons or the car or other acts of loyalty. These were stories about a man they never knew, and not the man they recognized as their father. Not the man who yelled more than spoke, who had no patience with any one in his home. The man who didn’t care who he hurt. What happened to that man? There’s always more to the story.

Like the story of a little Boy, born in 1928 to Armenian immigrants. His mom is young, only 25, at home with him every day, until the day she is never home again. It isn’t her fault; it isn’t his baby brother’s fault, even though she leaves when he arrives. And then his father is alone, with no family nearby, ill-prepared to raise two babies on his own. So he takes them to his wife’s sister in another State, to take care of; to raise. And what then, becomes of his father? Who, every night, comes home to a silent house, instead of one brimming with his wife and sons? Does he make himself a meal, or go to a diner? Does he have friends, perhaps friends’ wives who deliver meals, invite him over, try to fix him up with single women? Does he drink, maybe alone or in a neighborhood bar? Does he believe in God? And if so, does his young wife’s death disrupt that belief? Five years pass and his dad remarries. He is 43 and his new wife is 25, and it is time to reclaim his boys, now eight and five, to take them back home. A home they’ve never really known. Two years later, the Boy’s dad and new mom have a baby; he has a sister. The sister adores her brothers, but her mother does not. And how can she, this young woman inheriting little boys who are now removed from the only family they have ever known? Do those boys get to meet her before she becomes their mother? Did their dad visit them during those years? Does that Boy remember anything of his mother, the one he lost, now replaced by one he barely knows? Her food tasted of fear.

She cooked the way she lived – afraid. Every piece of meat, vegetable, even pasta had to have the contamination scorched out of it, lest it harbor disease. Botulism, trichinosis, streptococcus, staphylococcus, things that had nothing whatever to do with undercooked food, but just to be sure, she would broil and boil the shit out of it. Just to be sure. Dinner every night at 5:30 – gray, unidentifiable meat, mashed potatoes, vegetable and a glass of milk. “Drink your milk, goddammit,” my father would yell at Kathy. She was lactose intolerant; he was utterly intolerant. “It doesn’t give you a stomach ache – that’s all in your head,” he would yell. There was no reason to yell; it was a small table and just the four of us. I ate each food, one at a time, always saving my favorite for last. I still eat that way. “What the hell’s the matter with you,” he would yell. “It’s all going to the same place.” Kathy and I would constantly antagonize each other. Once, she put salt in my milk, just for fun. I took a sip and complained – “my milk tastes salty.” I forget how many times he yelled that I was imagining it before he tasted it for himself and proclaimed it to be salty. Because our parents prided themselves on being equitable with their daughters, we both got into trouble for that one. We got on her nerves, her perpetually frail nerves. One night she hit her limit and threw a plate full of food against the wall, then went to bed. It was an extreme reaction, but that was always her favorite kind. Anne Lamott once wrote about how hard it is to enjoy your dinner when you’re holding your breath. I could relate. Ian turned 13 today.

I remember being 13. I remember my mother forcing me to keep my unruly hair pulled into pigtails, my teeth half-way through the purgatory of braces, my ears freshly pierced. Catholic school uniforms, meant to level the playing field, doing no such thing. I remember falling in love with a boy named Scott. I remember sneaking out of Granny’s apartment at midnight to meet him in the stairwell and spend the next two hours kissing and talking, but mostly kissing. I remember Scott introducing me to Supertramp and David Bowie. I still listen to them both. I remember being told that when you fall in love at 13 it’s not really love. I remember thinking that was bullshit. It pleases me now, at 50, to know I was right. I remember trying out for cheerleading. I remember that my number was “7.” I still have that number, the one that was pinned to my shorts, in case I ever forget my number, or forget trying out for cheerleading. I remember thinking I would probably need to be a writer when I grew up. That I would have no choice. I remember at 13, being simultaneously sad, happy, resentful and ridiculous. I remember having no idea of who I was or was supposed to be, but always suspecting that I would be fine, no matter what. I remember realizing that I couldn’t trust my parents, that they didn’t have my back. I remember thinking, at 13, that I couldn’t wait to be 18. To be a grown-up. 13 was sweet, and difficult; it was exciting and confusing. It lasted forever, and it was over in a heartbeat. Ian is 13 and I have his back, and I think he knows that. But his 13 is his 13…. My mother is a problem I can’t solve.

People say, make peace with your mother. But, like Iran and North Korea, my mother doesn’t want peace; she prefers war. Or, at least, hostility. There was no disagreement, no single event which set the wheels in motion – nor is it the first time she’s chosen estrangement. She simply stops answering the phone when we call. She sees herself as a victim, the long-suffering mother/sister/daughter/wife– wronged by everyone she’s related to. She claims abandonment by her daughters, and without us to say otherwise, she can perpetuate this story. She hasn’t spoken to her sister in over 20 years; she wasn’t speaking to her mother or brother when they died, both in the same week. And she didn’t attend either funeral – she claims that no one told her they had died, which also can’t be refuted if no one speaks to her daughters. We send her cards, letters – and she sends them back, unopened. Kathy still calls her every day. Mom keeps her answering machine off, relying on caller ID to let her know who called. Or, who is calling. I have a philosophy – don’t complain about a problem unless you’ve exhausted every avenue of solving it. Some say there is no problem – she has cut us off, we should do the same. Except – she is 76 years old. Except, she lives alone, and, we care if she is okay. Except, that she has now taken every photo of her daughters and their sons, and had them delivered to Kathy’s house. Another chance to let us know that we have been boxed up and thrown out. It seems ridiculous because it is – but still, it is. And it goes on, and it will go on, and it is a problem I cannot solve. |

AuthorI was born in Oswego, NY, "I had always wanted to be a writer, but was impeded by the belief that to be a writer one had to be extraordinary, and I knew I wasn't. By the time I was ready to give up my academic career I had realized that while books are extraordinary, writers themselves are no more or less special than anyone else." The Thirteenth Tale by Diane Setterfield Archives

March 2024

Categories |

Sema Wray • Writer |

CONTACT |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed